"General Lee ... wishes you to evacuate the fort. You will not, without [an] order from me. I would sooner cut off my hand than write one" ~ John Rutledge

June 28th, 1776 - The defining moment in the birth of the Palmetto Republic was undoubtedly the hard-fought Battle of Fort Sullivan.

The fort's construction work was only half complete when nine British warships under Admiral Sir Peter Parker prepared to launch an attack on Charleston Harbor. Patriot reinforcements under General Charles Lee of the Continental Army had marched from North Carolina in anticipation of this aggressive move. Lee made an incorrect estimate that the fort would fall within thirty minutes and all of the defenders perish. Instead, the 2nd South Carolina Regiment under Colonel William Moultrie drove off the British in a famous victory.

It was the president of South Carolina "Dictator John" Rutledge that had ordered Moultrie to fight. One of the accidental factors in the victory was that the British cannonballs could not penetrate the fort's walls, which had been made out of palmetto logs packed with sand. Charleston had been saved, the men were heroes, and the palmetto was an enduring symbol of South Carolinian courage.

It was the president of South Carolina "Dictator John" Rutledge that had ordered Moultrie to fight. One of the accidental factors in the victory was that the British cannonballs could not penetrate the fort's walls, which had been made out of palmetto logs packed with sand. Charleston had been saved, the men were heroes, and the palmetto was an enduring symbol of South Carolinian courage.For the next seven years, nearly a third of the combat activities of the Revolutionary War occurred in South Carolina. This was partly because setbacks in the North had encouraged the Royal Navy to attempt to retake Charleston. As a result of the famous victory, Rutledge had become a central figure in the patriot struggle. His bitter disputes with Lee widened into a feud with the leadership of the Continental Congress.

South Carolina was considered large enough to be a viable independent polity. With the national legislature preparing a new constitution for a direct democracy to enfranchise property-holders, Rutledge decided that he had to seize the moment once again. Using his control of the militia, he took South Carolina in a radically different direction, following the example of Vermont, which continued to govern itself as a sovereign entity based in the eastern town of Windsor. Inevitably, the Union attempted the same tactics as it did in disagreement with Rhode Island by threatening a blockade with no trading. However, South Carolina was willing to pay this price for its independence.

A decade later, Rutledge led the Palmetto Republic's celebrations of Carolina Day, marking the tenth anniversary of the battle. By the time that representatives to the Constitutional Convention arrived in Philadelphia a year later, it was abundantly clear that the long-term future of South Carolina would exist outside of the United States. The original Articles of Confederation had recognized the thirteen members of the Continental Congress as having diverse interests and goals, but the idea had already taken hold that Americans had to form one single lock-step federal government.

This emerging consensus only validated Rutledge's political thought and inspired independence. Nevertheless, his outcome would cause border disputes with neighboroughing Georgia and North Carolina. Tension was to be expected, just as this was the issue of land claims with New York and New Hampshire that had prevented Vermont joining the Union. Rutledge hoped to build a Carolinian Confederation that combined all the former southern colonies. That herculean near-impossible task would fall to his firebrand successor, John C. Calhoun, at a time when the bonds of union had weakened and Georgia and North Carolina were beginning to dream of secession.

South Carolinian Jurist James L. Petigru would famously observe that "the territory of Palmetto is too small for a republic and too large for an insane asylum." During the nineteenth century, many US politicians would consider it a good thing that South Carolina was safely outside the Union. Ironically, Palmetto also struggled to trade with the increasingly anti-slavery British Empire. One of the key battlegrounds of the Revolutionary War, a State of South Carolina might well have been a key battlegrounds of a civil war if South Carolinian firebrands had fueled the calls for secession from inside the Union.

Author's Note:

In reality, Rutledge represented South Carolina in the Philadelphia Convention. He played a leading role resulting in his elevation to the Supreme Court.

Provine's Addendum:

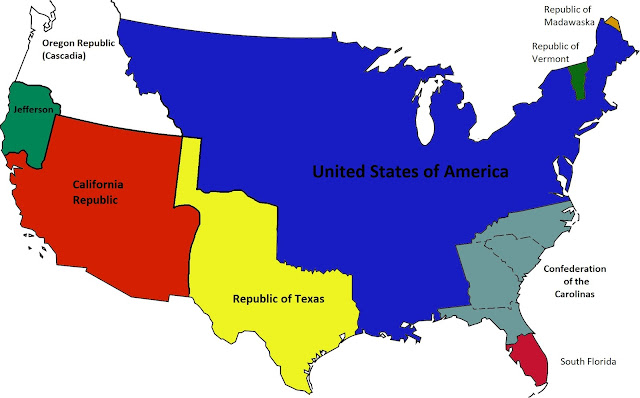

Over the course of the coming centuries, settlers would spread westward, causing friction with the Americans' neighbors to the north and Mexico in the south. After the disastrous War of 1812, both sides were nervous about another war caused by the disagreement of national boundaries in the northeast. Taking the success of landlocked Vermont as an example of a neutral barrier (that both could still attempt to manipulate through trade and diplomacy), the United States and British Empire both recognized the Republic of Madawaska in 1827. The hasty settlement of the Oregon territory claimed by both sides again left a wide gap. After much deliberation and influence, an independent nation was founded in 1843.

Meanwhile, disagreements in the southwest turned to violent revolutions. While the United States did not directly declare war for its own territory, Americans readily backed revolution in Texas in 1835 and another in California during the Second Texas-Mexican War in 1846. Both nations became close allies to the United States, although no one took suggestions of cessation seriously.

Even after the nineteenth century, further breaks would be seen in North American English-speaking nations. California had nearly lost its northeastern corner to a settlement dubbed "Deseret," but the anti-Mormon Nataqua War in the 1850s and '60s maintained dependence. In 1941, Oregonians and Californians who shared rural ideals felt ignored by their capitals and formed up a new allied nation called Jefferson, all under the careful guidance of the United States, which was eager to avoid a fight in the western hemisphere as Europe and Asia ground on in a second World War. Another cultural shift saw the southern end of the Carolian Confederation break away from Florida in 2008 with a new capital in Miami.

In the many years of organizing nations after the breakaway of the Carolinas, it is remarkable to historians that Virginia never vowed for independence, especially during the turbulent times after the Revolution. Virginia first grew by accepting and then giving away former North Carolinian claims to what became the state of Franklin. Later, Virginia would let go of its western claims to form Westylvania and Kentucky. Perhaps it was Virginia's dedication to work within the Union while championing local authority that prevented any notion of civil war and instead led to the plethora of US states, such as Superior above Lake Michigan, Empire in upstate New York, and Chicagoland separated from Illinois.