The Great Depression had ground on for years. While President Herbert Hoover had enacted breadlines and other minor alleviations for the out-of-work populace, the country as a whole continued to suffer unemployment and lack of cash. The people themselves began to call for direct aid, and none more vigorously than the veterans of the World War. In 1924, Congress had voted a bonus for each soldier in recognition of their service, giving one dollar for every day of domestic time ($1.25 for each day abroad) to a maximum of $500 ($625 abroad). The bonuses were paid via certificates and a trust fund, giving percentages until full payment was achieved in 1945.

By the troubled year of 1932, one-third of the payments had been made, and now Congress hoped to aid out-of-work veterans by advancing the payment to full. Hoover and his Republican allies were opposed to the idea, saying that it would strain the budget of the Federal government and take away funds needed for other relief programs. Veterans, however, pressed their representatives for the payment, and the House passed the Patman Bonus Bill to accelerate the giving of the money.

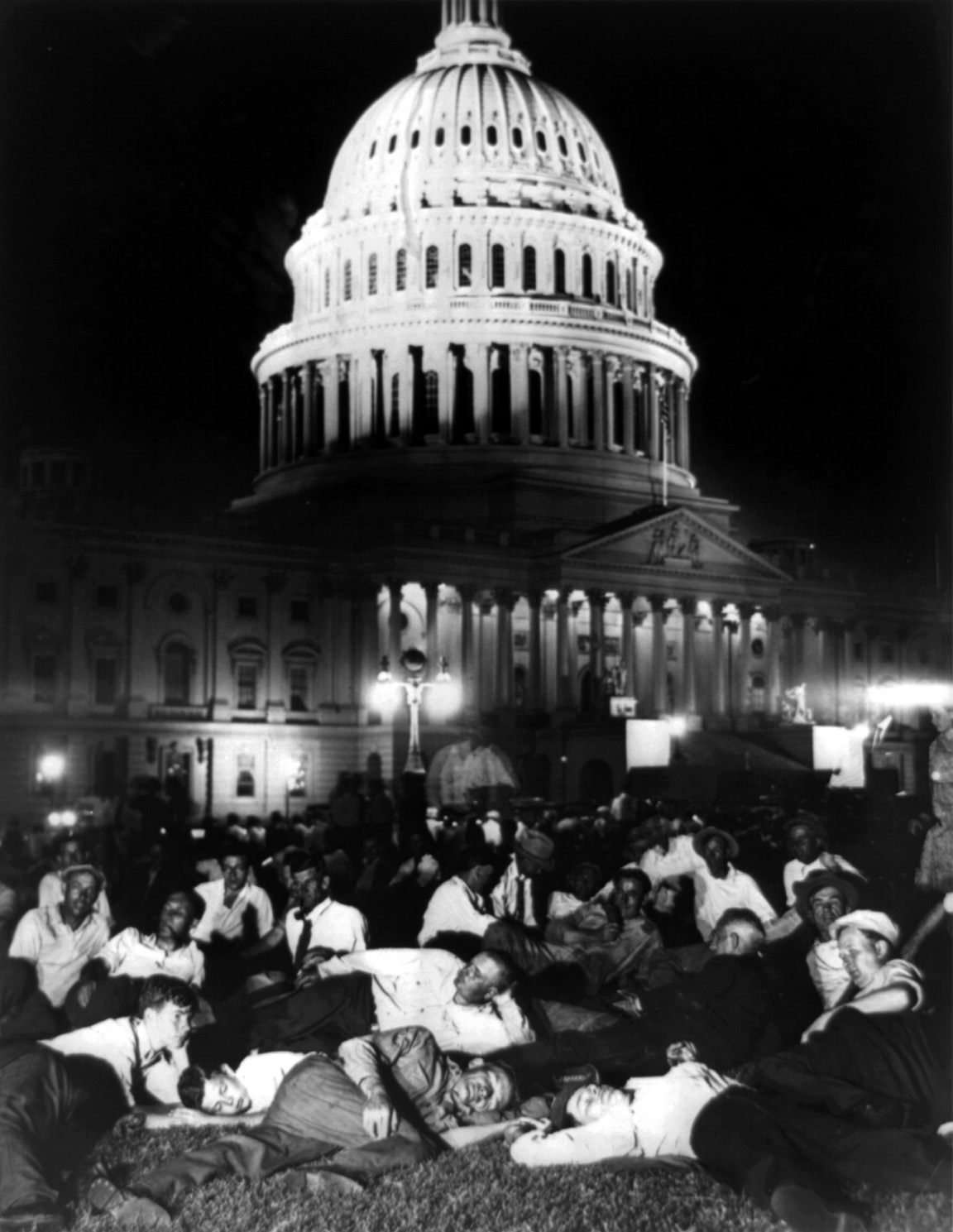

In June of 1932, the bill went before the Senate, and veterans marched on Washington to show their support for it. Seventeen thousand veterans came to the capital, bringing their families with them to total nearly 43,000 people. Most of them lived in Hooverville camps outside Washington proper, the biggest one being across the Anacostia River. Rather than disease-ridden slums, the camps were well organized with streets, clean water, sanitation facilities, and even parades. Despite the public support, the Senate blocked the bill, and now the “Bonus Army,” as they called themselves, began to protest in earnest for the funds that were rightfully theirs.

By July 28, the government had taken their fill. Protesters had marched on the White House, leading to a scuffle that resulted in police brutalizing several of them. Attorney General William D. Mitchell ordered the removal of all protesters from government property on grounds of trespassing. Police tried to clear a camp, but the veterans resisted. Shots were fired, and two veterans were left dead.

When he heard of the violence, Hoover decided to clear the district before things turned worse. He called General Douglas MacArthur from Fort Howard in Maryland with infantry and tanks from Fort Myer, Virginia, commanded by Major George S. Patton. The Bonus Army was in the midst of a march when the army arrived and took the appearance of the troops as a show of support. Instead, the cavalry and infantry charged, bayonets affixed.

Washingtonians who had come out to watch were horrified, crying “Shame!” at the army, but the soldiers took little notice. The veterans were chased back to the Anacostia Flats on the other side of the river, and Hoover ordered the troops to stop. MacArthur, however, ignored the President and took it upon himself to clean out the “communists.” Gas attacks, fire, and violent soldiers chased the veterans and their families out of the camp.

Before midnight, however, the veterans began to regroup. Making sure their families were safe in Maryland where the Federal troops did not have jurisdiction, they collected weapons and covertly marched back into Washington. As the army and police were busy breaking down the camp, the veterans organized their mob into ranks on the Washington Mall. Just as locals began to become suspicious of the nighttime activity, they charged into the Capitol and seized the building. Securing all exits, they advised the clerks, officials, and congressmen working late that they were not hostages and were free to go at any time.

MacArthur returned to Washington and began an assault up the main steps with his infantry. With shotguns, hunting rifles, and sheer moxie, the veterans held the doors and finally forced back the infantry, injuring many. As MacArthur began to call for artillery to blast open the Capitol, Hoover stopped him and removed him from command for disobeying orders. The infamous general would never serve with the United States Armed Forces again.

Major Patton offered to force entry with his tanks, but Hoover declined. Instead, a day-long standoff began as Washington police and Federal soldiers circled the building, but could not get close. Government workers, however, were allowed in, and the Senate was finally called to order. The block on the Bonus Bill was lifted, and the veterans collected their money and left peacefully. As soon as they were outside, they allowed themselves to be arrested.

National outrage over the incident poured into Washington. Some called for execution of the rebellious soldiers as traitors, but most were angry with the president and army for being so callous toward the veterans. Hoover would save face by shifting blame, dismissing Attorney General Mitchell and turning his whole campaign into the “cleansing” of the federal government. While his budget suffered greatly from the two-billion-dollar shortfall, he refused to go over-budget more than absolutely necessary. Touting thriftiness and earning wherever possible, as well as gaining a great deal of support from veterans, Hoover would narrowly win the 1932 election over New York Governor Franklin Roosevelt.

Hoover's next term would be four more years of struggle for the country. Prohibition would be overturned by Congress in 1933, but the economic issues would not be solvable by mere tenacity. Relief efforts struggled to keep up with unemployment. In the elections of 1934, people had had enough, and Democrats were voted into power in Congress. The Great Depression did nothing but worsen.

In 1936, FDR came into office overwhelmingly, and he brought his New Deal into full swing. Ignoring budget constraints, FDR started enormous works projects to employ as many of the unemployed as possible. The changes were radical, which was just as well since radical groups became increasingly powerful over the country. By 1940, people said that the US was all but socialist in name with resources in food, oil, electricity, public water, and health insurance all regulated by the government.

While the populace was suspicious of such control in the Land of the Free, World War II would solidify FDR's political maneuvers. Through the second half of the twentieth century, so much of the basics of American life would be guaranteed that LBJ's New Society would create a welfare state of nearly one-half government employees (or, as many social critics would call them, “government slaves”).

In 2002, President Albert Gore would even expand American human rights to guarantee Internet service.

–

In reality, the veterans did not regroup and counterattack. The Bonus Army maintained a presence in Washington, but they did not trifle with protests against Hoover again. The incidents would haunt Hoover and doom him in the 1932 election. FDR and his New Deal programs would alleviate much of the poverty of the Great Depression, though it would balance against capitalism and private innovation that Americans have always taken as a part of the national spirit.

No comments:

Post a Comment