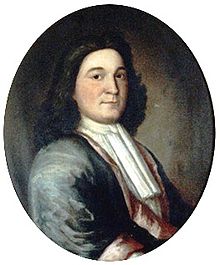

Upon his confirmation as Governor of the Massachusetts colony on May 4, 1692, William Phips found a state of uproar. Settlers hungry for land to feed their growing families pushed north and westward into the frontier, provoking attacks from the Indians. Internally, panic had seized the town of Salem and seemed to be spreading as witchcraft had violently found its way into the colony.

On May 29, he ordered a Court of Oyer and Terminer to settle the matter. He appointed judges to listen to the accusations promoted by girls afflicted with seizures and weigh their opinions against the supposed witches. By June 8, Bridget Bishop was the first witch convicted, later to be hanged. While Phips, the former sea captain, anticipated the court to be the end of witchcraft, it only spread more panic. Suspicions arose that the fear of witches brought false accusations that led to great advantages when the accusers seized valuable property.

Through the summer, witch after witch was accused and many were hanged. Several died in prison and others while undergoing torture to secure confessions. After all, if a witch were to confess, the soul might be saved while the body was punished. Better an innocent soul to be in Heaven than a guilty person freely walking the earth under the Devil’s domain. While the puritanical logic seemed sound, the system came under increasing question.

The Mathers, Cotton and his father Increase, were some of the first to speak up over the questions of “spectral evidence” used in the court. As early as June 15, Cotton Mather, wrote to the court warning of hearing testimony that was “spectral”, or simply dreams and visions made by the accuser that could so easily be fabricated. His advice was mostly ignored, though the name was held in esteem. Cotton is often understood as something of the beginning of the crackdown on witchcraft by the publication of his book Remarkable Providences in 1688, which brought the notion of warning dreams to the minds of so many.

On October 3, Increase Mather, who was President of Harvard College, publically denounced spectral evidence. When he had heard the opinion of Mather, Phips decided that the rampant trials had gone so far as madness. He placed a moratorium on proceedings and cited the “danger some of their innocent subjects might be exposed to” based on this lack of evidence that may simply have been fear-mongering by the accusers in a letter to the Privy Council of the Crown. In same letter, he outlined his plan to begin a new system of finding and judging witches.

The same day, October 12, Phips asked Cotton Mather to head an inquisition to establish a logical and “scientiffik” method of determining witchcraft. Cotton agreed, and the formal study of witch-hunting came to the colony. Initially, Cotton worked on the cases at hand, advising the Court of Oyer and Terminer until its dissolution weeks later. By the end of the month, most of the prisoners were released and higher court proceedings ruled further accused witches innocent. Several witches, however, were proven guilty.

In 1683, Cotton published Wonders of the Invisible World, a guide to his methods of witch-catching. He drew upon numerous sources including first-hand accounts from Salem as well as Glanvill’s Saducismus Triumphatus. Cases against witches could only be drawn on concrete grounds, of which Cotton gave numerous examples. Over the next year, the hysteria of witchcraft settled to vigilance, and Cotton’s investigators traveled throughout the colony researching potential Sabbats, familiars, and unruly women suspected of cavorting with evil powers.

Through the eighteenth century, the numbers of witches found among colonists would dwindle, especially as laws limiting the powers of women were enacted. The investigators gradually shifted their attention to obvious witches in the shaman of the Indians. In numerous altercations, these shamans would fall under assassination, attack, and arrest to end their devilish ways. In the times leading up to the Revolution, the investigators used their skills to root out rebel spies among the Loyalists, leading to a brutal covert war of military intelligence. The American victory ended the work of Mather’s Investigators, and lingering anger over their dominance aided in the passing of many parts of the Bill of Rights, especially in the First (which legalized white magic as religious practice), Fifth, and Seventh Amendments.

–

In reality, Phips simply shut down the witch hunt. He prohibited arrests and worked toward the pardon of many supposed witches. When the courts were dissolved, the hysteria died away, leaving a lingering spirit of guilt. August 26, 1706, Ann Putnam Jr, who was not one of the first but one of the loudest accusers, stood before Salem Village church and asked forgiveness for her part in what had been a very dark prank.

No comments:

Post a Comment