In England's Revolution of 1688, often termed the “Glorious Revolution”, the Stuart dynasty was removed from the English and Scottish thrones once more, this time deposed by William of Orange at the invitation of Parliament. The Catholic kings of a Protestant nation had been a struggle through the seventeenth century, but many in Britain felt that the Stuarts would be best upon the throne, especially as non-English-speaking Germans from Hanover began to rule. The Stuart Cause would continue, even after “The Fifteen”, a bungled invasion by James III & VII after which the Old Pretender was no longer welcome in France as an embarrassment.

Prince Charles Edward Stuart (fondly known as “Bonnie Prince Charlie”) had been trained for war since his birth. He witnessed sieges, studied with commanders, and took up pursuit of the generalship that would win him back his throne. While his father was the exiled king, James III & VII still had enough influence to persuade France into sending an invasion fleet in 1744. In preparation, Prince Regent Charles went to Scotland and began to raise his army of supporters. While the French invasion never materialized, Charlie decided to carry out the reconquest of Britain himself in 1745.

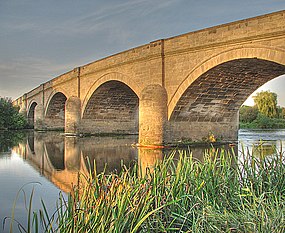

With two ships and an army of eight men, Charlie landed at Eriskay on July 23. Finding great support among the Highlanders, Charlie raised his father's standard and formed up an army large enough to subdue Edinburgh. At Prestonpans on September 21, Charlie met with the only government army to stand against him in Scotland, which he soundly defeated, inflicting ten times the causalities his force took. From there, he pressed south, moving practically unopposed with 6,000 men through Cumbria and Derbyshire to Swarkestone Bridge. There, word said that few supported him in the south and, worse, the government was building a mass of force to counterattack. Charlie's commanders advised him to turn back and raise more of his own support.

Charlie decided to ignore them and pressed southward while momentum was with him. It was found that few did support him in the south, but few supported the Hannovers as well. As winter settled, Charlie made for London, hoping to besiege the city during its hungriest time. His only obstacle was a force comparable in size to his own, though hastily assembled, led by King George II's son, the Duke of Cumberland. They met at Hatfield on December 18, where Charlie's Highlanders made use of the ancient woods to minimize the effect of the government cannon. When the battle was won, Charlie seized the cannon and turned it on London for the winter siege.

By spring, the city was in an uproar against Parliament. Without hope of fresh food coming that spring, the winter starvation would grow even worse. Charlie welcomed anyone who would desert the city and join his cause, strengthening his ranks with generous Christmas and New Years' feasts. Finally, on April 16, Parliament conceded and voted to reinstate the House of Stuart and oust George II. Charlie's father James would be crowned later that year and rule until his death in 1766. The aged James was feared as being a Catholic tyrant, but he proved largely ineffectual, his most vivacious act being to keep Britain out of the Prussian War, where Frederick the Great established himself as a power on the Continent.

Charlie, meanwhile, traveled the British Colonies in hopes of expansion. He toured the Americas, also helping to establish the legitimacy of the Stuarts, and joined Robert Clive on his second journey in India. During his time in England, he converted to Anglicanism, which enraged his father but set many British minds at ease. Upon being crowned in 1766, Charles III began ambitious projects to expand British trade and endorsed exploration for new routes and potential settlements, especially in North America and in the Pacific with Admiral Cook's five voyages. His rigorous expansion inevitably led to further wars with the Dutch and French, expensive naval campaigns that drained the treasury of all.

When Parliament attempted to levy heavier taxes, uproar rose among the American colonists in the early 1780s with calls for representation, perhaps even independence. It is said that Charlie was fearful of losing his crown after fighting to win it, and he went quickly to work adding American seats to Parliament to guarantee his support. His “weakness” would be severely criticized by many Tories, but the heavy hand of the French king Louis XVI would lead to the brutal revolution in 1791.

Charlie stayed quiet through the remainder of his reign, depending more upon prime ministers such as William Pitt. His son Charles IV succeeded the throne upon his death in 1798, the same year the Egyptian War sparked as Republican France attempted to strike at India through the Suez. Upon the sound defeat of France and the seizure of many of its colonial claims, the nineteenth century would stand as the next golden age of Britain, continuing Charlie's legacy of progressive economics and social liberality.

–

In reality, Bonnie Prince Charlie retreated from the south at Swarkestone. The retreat gave time for the Duke of Cumberland actually to form an army such as they feared, and he would take up pursuit of Charlie until the Young Pretender's defeat at Culloden on April 16, 1746. Charlie would escape from Scotland in disguise and return to exile as a broken man. He took mistresses, reportedly drank heavily, and his physical abuse of his wife Princess Louise of Stolberg-Gedern drove her away. His brother Henry IX became a cardinal, outlived him, and, never taking a wife, would be the last of the Royal House of Stuart.

There is a whole Stuart line after Henry running till today. The current Stuart heir Francis of Bavaria is 87 and gay!

ReplyDelete