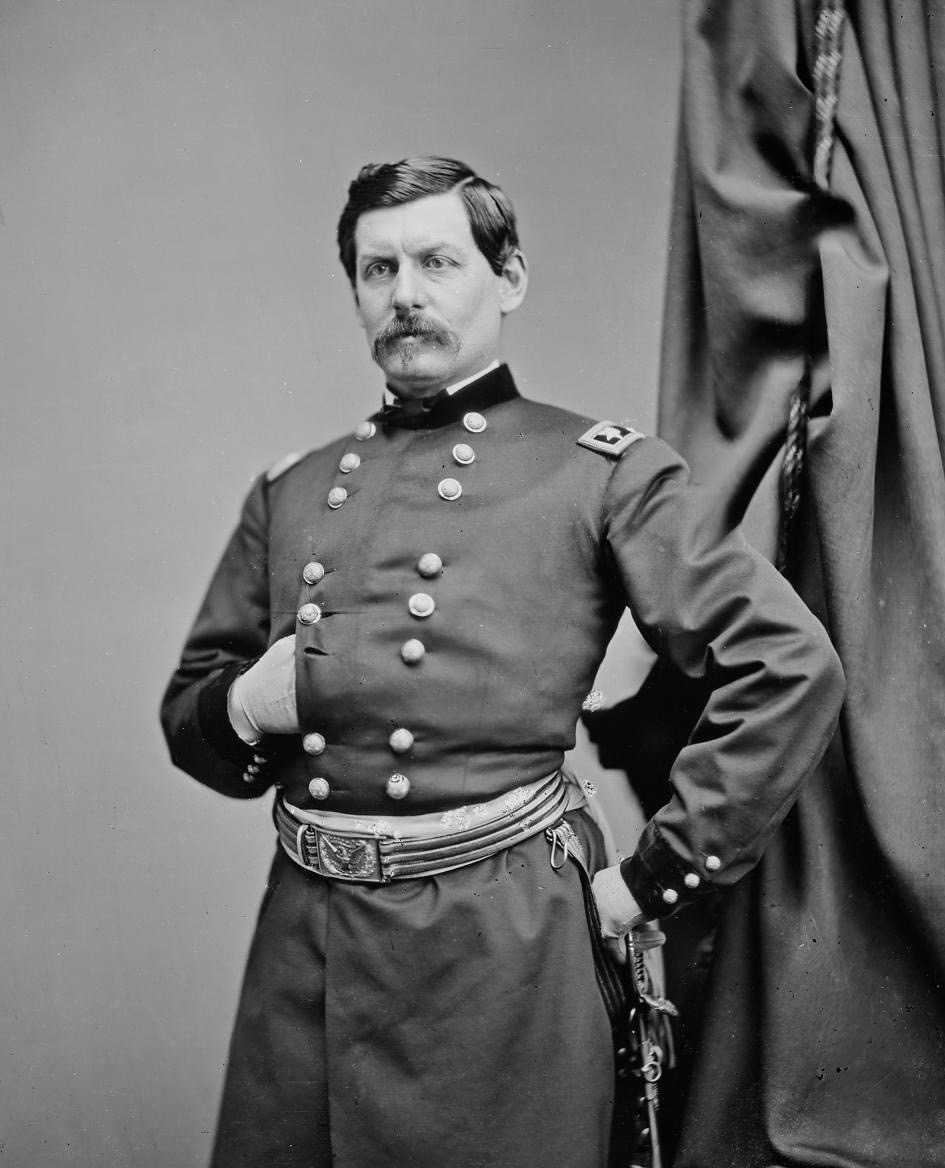

After not even two weeks of being General-in-Chief of the Union Armies, General George B. McClellan was dismissed from his position after repeated faux pas. President Abraham Lincoln, Secretary of State William H. Seward, and presidential secretary John Hay came by McClellan's house for a strategy meeting. The general was out, so the men waited. An hour later, McClellan returned but did not acknowledge them, and, after another half hour, his servant finally told the president that McClellan had gone on to bed. Lincoln was initially very calm, as he would typically be despite the trials of his presidency, and at first determined "better at this time not to be making points of etiquette and personal dignity." When word slipped that McClellan had privately referred to Lincoln as a "baboon" and "gorilla" and Seward as an "incompetent little puppy," Lincoln's uncustomary temper rose, and he fired his general-in-chief, demoting McClellan simply to commander of the Army of the Potomac.

Lincoln, however, put himself into dire straits. His military was hardly ready, but the populace was unsure whether a war to keep the Union united would be worth it, and he needed victories to keep the people in ready. General Winfield Scott, who had served with the US Army since before the War of 1812, had retired October 31 due to "health reasons" of being seventy-five years old. Other commanders might have been available, but Lincoln needed someone he was certain would be brash and wield the available army to the fullness of its effect. He recalled meeting Colonel William Tecumseh Sherman, one of the most effective commanders at the Battle of Bull Run that June. Lincoln had been so impressed that he promoted Sherman to brigadier general of volunteers.

Sherman, however, was unnerved by the war. The defeat by Confederates had caused him to question the abilities of Union soldiers as well as his own competency as a commander, despite his bravery even after taking grazing bullet wounds to his shoulder and knee. He had been assigned to Robert Anderson in the Department of the Cumberland and that October had replaced Anderson due to ill health. Sherman had been promised by Lincoln not to be given such authority so suddenly, and it began to wear on him. He was increasingly paranoid of Confederate resources and sent constant requests for more supplies from Washington. After a review by Secretary of War Simon Cameron, the press turned against him, noting his pessimism and what would be later described by psychology as a "nervous breakdown." He was relieved of command and sent to St. Louis, where he would receive his summons to Washington by Lincoln as a new general-in-chief to concoct the strategy for defeating the South.

Sherman arrived in Washington and immediately pleaded with Lincoln (directly as well as through his brother, Senator John Sherman) that he was unfit for command. Lincoln recalled his reservations about McClellan's ability to be both general-in-chief while still operating as an army commander, to which McClellan assured him, "I can do it." The president was tired of generals who questioned his decisions as commander-in-chief, and Lincoln wrote Sherman a direct order to take command. Sherman committed suicide December 23, 1861, under the pressure.

It would be a severe strike against Lincoln's administration and public opinion about the war. Further, Lincoln was once again stuck without a commander. Frémont had proven overly aggressive in Missouri that November, turning Lincoln to the third most senior general in the Army, Henry Halleck, who had just replaced Frémont in Missouri. Halleck soon arrived in Washington and proved an able administrator, though Lincoln would be frustrated over his lack of action in the next years, referring to Halleck as "little more than a first rate clerk." The Union struggled to make any progress in the East, but the Western theater with its eager General Ulysses S. Grant returned numerous victories. Winfield Scott's "Anaconda Plan" eventually began to choke out the South, who suffered Pyrrhic losses in its invasion of Pennsylvania under Lee, and Grant was made the new general-in-chief in 1864 with Halleck being "kicked upstairs" to Chief of Staff.

Grant put forward Lincoln's plan of total war to break down Southern infrastructure and keep potential reinforcements pinned. The taking of Atlanta by General George Henry Thomas on October 2, 1864, came just in time to guarantee Lincoln's second election, and Thomas would lead the careful and slow demolition of Southern communication, transport, and industry. However, shortly after the end of the war with Lee's surrender in June of 1865, the superficial damage would be easily repaired. Lincoln's assassination came as a harsh blow to the South, but Thomas's gentlemanly use of Army resources to enable Southern rebuilding did much to aid feelings in Reconstruction after the notions of him being a "traitor" to his native Virginia faded.

Andrew Johnson battled through the rest of Lincoln's term, and in 1868 Grant would win the presidency. While dealing mainly with the issues of the South, he would also be notably genial toward Native Americans. His use of treaties restricting buffalo hunts came too late to preserve the food supply entirely, but he would continue his overall attitude toward Natives as "harmless" and "peaceful" until "put upon by the whites" and prevent as many armed altercations as he could.

--

In reality, Lincoln allowed McClellan to continue as general-in-chief until the failure of the Peninsular Campaign. Sherman would be given leave not long after the Cincinnati Commercial referred to him as "insane" on December 11, 1861. He soon return recuperated, taking up service under Grant, whom he would aid in victories such as that at Chattanooga. When Grant became general-in-chief, he gave Sherman command to take Atlanta and approved the later March to the Sea, which saw scorched earth tactics of utterly laying waste to the South from Atlanta to Savannah. After the war, Sherman would be put in charge of the Military Division of the Missouri, where he would write to Grant that "hostile savages like Sitting Bull and his band of outlaw Sioux ... must feel the superior power of the Government" and "we must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children."

No comments:

Post a Comment