March 2, 1955:

Teachers at the segregated Booker T. Washington High School led a series of studies for Negro History Month. Topics included women's rights activists such as Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth.

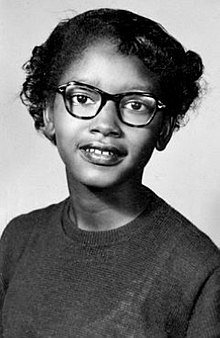

Already a member of the NAACP Youth Council, a fifteen-year-old student called Claudette Colvin had been spurred into an act of civil disobedience by her educators. Joined by a pregnant woman called Ruth Hamilton, she stubbornly refused to give up their seats to whites when ordered to by motorman Robert W. Cleere. Ignoring insistence upon her constitutional rights, he made good on his threat to call the police. After a brief struggle that turned increasingly violent when Colvin was kicked by one of the officers, she was forcibly removed from the bus and never seen alive again.

Witnesses of the event raced to the house of her mother, Mary Ann Colvin. She called the local pastor, Reverend H.H. Johnson, who owned a car and together they drove them to the women's penitentiary in Atmore only to discover that she had died of head injuries. The local community was enraged and meetings were held throughout the night attended by members of the Baptist Church, NAACP and also the Communist Party, working in unison.

The

FBI were particularly concerned about the activities of one Communist

called Raymond Parks, whom they suspected of agitating for a mass event

such as a Bus Boycott. Governor "Big Jim" Folsom moblised the Alabama

State Guard, but events had already taken their own course. A series of

grisly murders occurred during the night including Parks and his wife

Rosa, who was NAACP Secretary, and also local NAACP president E.D. Nixon.

One of the perpetrators, Jim Blake, would later claim that these violence

actions were necessary to save Jim Crow.

The

FBI were particularly concerned about the activities of one Communist

called Raymond Parks, whom they suspected of agitating for a mass event

such as a Bus Boycott. Governor "Big Jim" Folsom moblised the Alabama

State Guard, but events had already taken their own course. A series of

grisly murders occurred during the night including Parks and his wife

Rosa, who was NAACP Secretary, and also local NAACP president E.D. Nixon.

One of the perpetrators, Jim Blake, would later claim that these violence

actions were necessary to save Jim Crow.With NAACP and Communist Party organisations shattered, the church of Michael King Jr. became a focal point. He was an active committee member of the Birmingham African-American community that was overseeing the legal challenge to bus segregation. From his pulpit, he began to call increasingly for federal funding in grants for the reopening of colonization in Liberia, founded in West Africa by abolitionists during the early nineteenth century. Only a few thousand separatists, mostly escaped slaves and free men, had made it to the capital of Monrovia (named after the-then US President). Being lighter-skinned and culturally distinct, they had their own assimilation problems. Yet they founded a power structure that their descendants still held on to at the time of the Montgomery Riots, when it was the second largest black settlement after Freetown, Sierra Leone. Even though Liberia was no more an empty "Promised Land" than the biblical Canaan, King's ideas were warmly welcomed in Monrovia. But with neighboring countries moving fast towards independence from colonial powers, some feared for the viability not just of the larger colony, but the host country itself. Would this project actually lead to a greater Liberia, an African Tiger economy, or would it become even more two-tier, perhaps corrupted by the greater resources of the separatists ruling the country? Others would argue this was the same confidence issues that had been bred into African consciousness by white governments. But in retrospect, most would agree that the Montgomery Riots had been a turning point.

King, himself of Irish Ancestry, was realistic; he fully realised that Liberia could never resettle the whole African American community. In fact, he actually hoped for a wider settlement across West Africa in which millions of African Americans would re-start a historical process begun by the founders of Liberia back in 1822. But, inevitably there were resistance from both sides, because a costly government program would of course require both resettlement as well as construction and infrastructure. Consequences too for those that stayed behind, reduced in number by the successful separatists. But ultimately, "Back to Africa" would slowly take shape and over the following decades hundreds of thousands of families would cross the Atlantic and make a significant impact upon future history. Kennedy, and then Johnson and Nixon, would come to rely upon the promise of passage payments as a means of incentivising the African Americans soldiers that made up the 12 percent of the Armed forces sent even further afield to fight (mostly in the infantry) in a small country called Vietnam.

Author's Note: in reality [reports Jeff Provine] it was the later arrest of Rosa Parks that would serve as a great symbol for the growing campaign to end segregation, seemingly better suited than the arrest of Claudette Colvin in a similar incident a few months earlier. With Parks as a symbol and Colvin's case victorious in federal court for Browder v. Gayle, the road to equality began to open by means of civil disobedience.

No comments:

Post a Comment