On December 11, 1879, Sir Henry Bartle Frere outlined an ultimatum for King Cetshwayo of thirteen points created around the increasing difficulties with the British, the Afrikaners, and the Zulu all working to cohabitate the southeast corner of Africa. Many of the points were the surrender of Zulus who had committed crimes across the border and were sought for trial in Natal courts. Other points outlined a system of social change for the Zulus, including marriage rights, treatment of Zulus converted to Christianity, and the disbanding and modification of their army. Still others insisted on a British Resident adviser to determine Zulu law such as exile and any legal activity involving a European. The ultimatum was drastic, and both Frere and Cetshwayo knew it was unacceptable. The month deadline passed, and Frere ordered Lieutenant General Frederick Augustus Thesiger, 2nd Baron Chelmsford, to invade with 15,000 men.

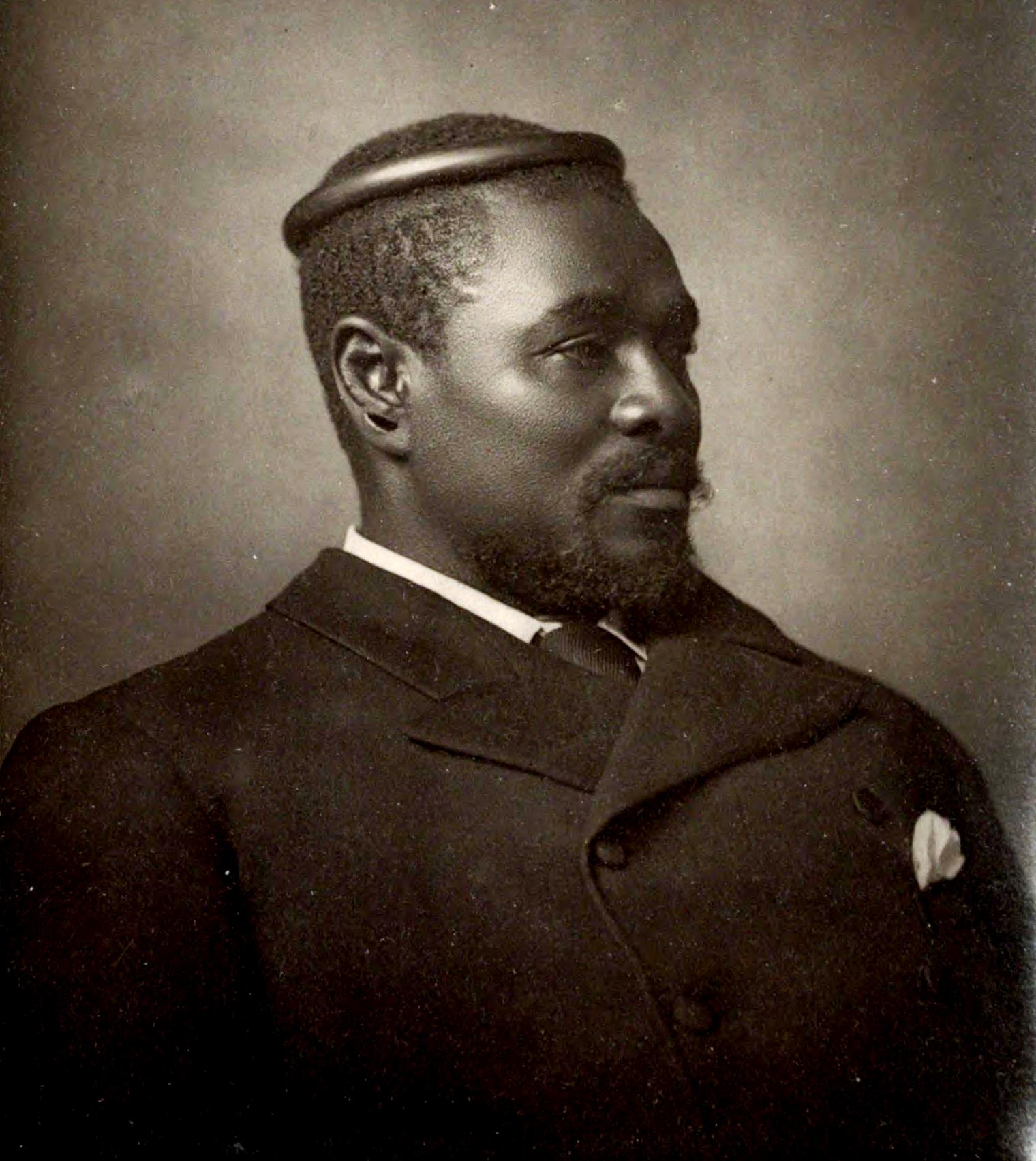

As British troops crossed the Tugela River into the Zulu kingdom, they were met with a delegation led by King Cetshwayo himself. Chelmsford was shocked to see a diplomatic approach from Cetshwayo. The Zulu were a warlike people, Cetshwayo’s great-grandfather Shaka had revolutionized their army and conquered neighboring tribes to build a powerful kingdom as Europeans began to arrive. They had subordinated the Swazis, and Cetshwayo had impressed the Europeans diplomatically enough to seize ceded land. He flexed these skills in strong diplomacy again to Chelmsford, stating (through translation as well as from a legal stance provided by Anglican Bishop Colenso, who sought peace among the troubled nations) that the invasion was illegal, and he demanded to speak with the Britons’ queen, inviting her to his capital at Ulundi.

The action was unorthodox, but Chelmsford’s civility forced him to comply. He made camp along the river and sent messages to Frere. The latter was outraged at Chelmsford’s failure to follow orders, but by then the invasion had come to the notice of Sir Michael Hicks Beach, Secretary of State for the Colonies, who forbade it. Frere argued that, without the Zulus standing down their army, confederation as had been seen in Canada could not take place. Hicks Beach replied that, without diplomacy, confederation would only be by war.

Word returned to London about the request, and Parliament debated the matter of recognizing officially the Zulus rather than treating them as an uncivilized power on the verge of colonization. While a trip for the aged queen was out of the question, Victoria recognized the generosity of the king. She requested Frere recalled as a troublemaker, and Prime Minister Disraeli agreed. Frere begrudgingly left Africa, and the more local John Molteno of Cape Town established a new government based in organizing southern Africa diplomatically. The Boers were granted their constitution for Transvaal thanks to Frere’s actions upon his return to London, heading off a potential war and saving his legacy.

Over the next decades, unionism would gradually take root as Molteno’s policies of economic stimulus brought railways and manufactured goods to the Zululands and protectorates of the Orange Free State and Transvaal. Zulu were given precedence over the rebellious Xhosa, and local chiefs were rewarded for development of their lands. Rampant exploitation as seen by Rhodes and others gradually died away as ideals of workers’ rights and freedom from taxation grew, such as the Demonstration Rallies of 1906. The fight for rights and equality became a model for other colonies, specifically India whose leader Mohandas Gandhi witnessed the actions while supporting advances by Indian immigrants there as a young lawyer.

Though true equality is a difficult political point to reach, the Union of South Africa has shown great strides in establishing a complicated federation of native kingdoms, former British, Dutch, and German colonies, and districts stretching from Cape Town to Lusaka. In 1962, the young and popular Rolihlahla Mandela was named Prime Minister, the first African to do so, but certainly not the last.

–

In reality, Cetshwayo defended his kingdom by warfare. Using many of his great-grandfather’s tactics, he repelled the British invasion, but Chelmsford regrouped in Natal that summer, leading to British victory in August. The First Boer War started soon after, and the settlers were placated until the longer and much more devastating war between 1899 and 1902. Insurgency would continue even after de-colonization, which would lead to the dire times of Apartheid as the placing of one people over another was forced as the legal norm.

No comments:

Post a Comment