Point of divergence:

Bismarck's expansionist strategy isolated Prussia's enemies by attacking them separately. This prevented confrontation with the coalition of forces that had defeated Napoleon, notably with the late arrival of Prussian troops winning the Battle of Waterloo. However, in this alternate history scenario the strategy is flawed, backfiring when capitulation goes too far. We imagine that the Habsburgs, similar to the Bonapartes, lose their throne, resulting in the unintended collapse of the Austrian state.

Jan 18, 1871 -

Otto von Bismarck, the "Iron Chancellor" of Prussia, paid the ultimate price for his disastrous political miscalculations in attempting to unify Germany. Dismissed by Kaiser Wilhelm Hohenzollern, he was not even present when the German Kaiser's realm was proclaimed at the Royal Palace in Berlin.

The supreme irony of this humiliating exclusion was that the formation of an all-German supranational state was an over-achievement that he would not have welcomed. Nonetheless, it was Bismarck, rather than Wilhelm, that was the real architect who had brought the Reich into being. After all, he had led the formation of the North German Constitution for a loosely organized confederation in which sovereignty rested with the individual states as a whole. This political re-arrangement was only made possible by the successful outcome of the Austro-Prussian War, which dissolved the German Confederation and allowed Prussia to annex many of the smaller German states. The unforeseen consequence was that the crushing victory at Sadowa caused the collapse of majority-Catholic Austria from a great power. A series of revolutionary events inexorably led to not only the dissolution of the Austrian-led German Confederation states but also the fall of the Hapsburg monarchy that had ruled Central Europe for centuries and in its current form since Napoleon dismantled the Holy Roman Empire.

Even worse was the unfortunate timing with the dissolution occurring during the latter stages of the Franco-Prussian War. The failed devolution attempt at power-sharing with Hungary had necessitated a reorganization of the sweeping Hapsburg territories. This political initiative had created a crown land of Cisleithania with Vienna as the capital. But now after the break-up of the Hapsburg Empire the nascent Republic of Cisleithania desperately needed protection from a vengeful neighboring Hungary.

The supreme irony of this humiliating exclusion was that the formation of an all-German supranational state was an over-achievement that he would not have welcomed. Nonetheless, it was Bismarck, rather than Wilhelm, that was the real architect who had brought the Reich into being. After all, he had led the formation of the North German Constitution for a loosely organized confederation in which sovereignty rested with the individual states as a whole. This political re-arrangement was only made possible by the successful outcome of the Austro-Prussian War, which dissolved the German Confederation and allowed Prussia to annex many of the smaller German states. The unforeseen consequence was that the crushing victory at Sadowa caused the collapse of majority-Catholic Austria from a great power. A series of revolutionary events inexorably led to not only the dissolution of the Austrian-led German Confederation states but also the fall of the Hapsburg monarchy that had ruled Central Europe for centuries and in its current form since Napoleon dismantled the Holy Roman Empire.

Even worse was the unfortunate timing with the dissolution occurring during the latter stages of the Franco-Prussian War. The failed devolution attempt at power-sharing with Hungary had necessitated a reorganization of the sweeping Hapsburg territories. This political initiative had created a crown land of Cisleithania with Vienna as the capital. But now after the break-up of the Hapsburg Empire the nascent Republic of Cisleithania desperately needed protection from a vengeful neighboring Hungary.

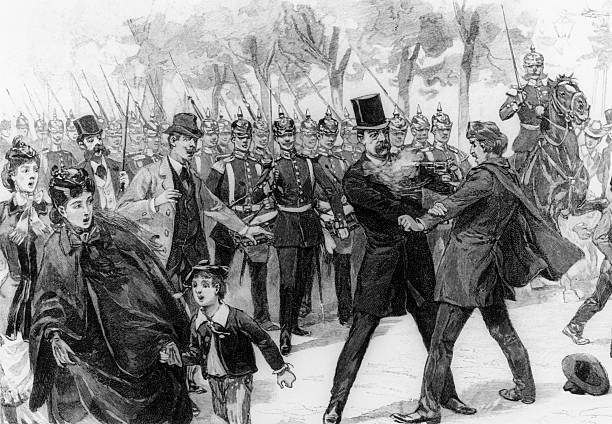

The defenseless Austrian state was forced to take the fateful step of joining the Empire on the sole condition that the hated Bismarck was replaced. After all, in Vienna he was seen as the architect of the Austrian downfall, as evidenced by the assassination attempt by Ferdinand Cohen-Blind.

Delicate negotiations between Berlin and Vienna successfully averted religious tension between the Lutheran North and the majority Catholic South (including Bavaria, albeit there were some Lutherans in the South). They also prevented a revanchist future Hapsburg attempt to usurp a rump kingdom in Cisleithania. Based upon the reconsideration of these unification factors, it was determined that the original location of the proclamation in Paris smacked of Hohenzollern adventurism. To bring the focus back to confederation, the ceremony was moved to Berlin to respect the odd composition of the Reich into a realm of kingdoms and republics. In hindsight, Prague, Hanover, or Magdeburg might have been more humble choices.

By preventing internal strife these fateful decisions did unite a German Empire under Hohenzollern leadership, but the flawed strategy of subduing neighboring states had unforeseen consequences. Overreach was surely the biggest mistake, and the unnecessary acquisition of Alsace-Lorraine with the subsequent Germanization of the French became a flashpoint. Hungary allied with the Third Republic, leading to a wider continuation war in which the victorious Germans gained even more French territory.

Of course this repeat humiliation made matters worse as not even Bismarck had been in favor of colonies. Had he become Reich Chancellor instead of zu Stolberg-Wernigerode, then he certainly would never have agreed to Denmark's offer to join the Empire in return for the territories it lost in the Second Schleswig War. With events racing out of control at this dangerous moment, it became apparent that the Reich's ultimate ambition was to unite all Europeans into a loose multinational confederation ruled by Berlin. This of course was nothing less than a supersized Hohenzollern version of the Hapsburg rule in central Europe, and a growing realization set the stage for the outbreak of general war. A bitter and regretful Bismarck would famously make a note of Proverbs 16:7 in his diary, "When a man's ways please the Lord, he makes even his enemies to be at peace with him."

Author's Note:

In reality, the proclamation occurred in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles with Bismarck center stage and the Hapsburgs not even present. Napoleon III would be exiled to London, where he would die in 1873 with his last words, "We were not cowards at Sedan, were we?" This compares with "We were not cowards at Sadowa, were we?", the final worlds of ATL Austro-Hungarian general (Feldzeugmeister) Ludwig Benedek speaking to Prince Albert of the Kingdom of Saxony.

Provine's Addendum:

The German acquisition of Alsace-Lorraine proved to be the ongoing cause of French-German enmity that Bismarck warned. Commentators of the time such as Karl Marx and later commentators like Winston Churchill felt much the same, although Heinrich von Treitschke wrote, "We Germans who know Germany and France know better what suits the Alsatians than the unfortunates themselves." The dismissive attitude prevailed with most of German attention focused on the Austrian lands, particularly the Austrian Littoral where German railroads could reach the Gulf of Trieste as a Mediterranean port, opening whole new markets. The economic surge chided Italy, mirroring the displeasure of Hungarians and Russians sharing the large border with Germany in the east, especially with the former Austrian lands with large Polish and Ukrainian populations scooped up by Germany as they seized Cisleithania.

France worked its diplomacy to build up an Entente against predicted future German expansion. Germany, meanwhile, sought to break the ring around itself with allies in the Ottoman Empire, carefully balancing the independence of Serbia in the Congress of Berlin and the establishment of the Principality of Bulgaria. In the Balkans, the Bosnian Question lingered as Hungary wished to hold onto its reaches of the former empire or grant the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina independence. Even Britain joined in the Entente, suspicious of German interests overseas with its expanded naval operations past Denmark into the North Sea.

The Great War broke out early in the twentieth century with the assassination of Wilhelm, German Crown Prince, while touring the empire (ironically to promote peace). Italy ultimately remained neutral, although Romania was pulled into the chaotic war in the Balkans between Russian-Bulgarian and German-Ottoman influences. The war in the west quickly became a stalemate with long trench lines in France and naval harassments across the North Sea. The east saw intensive bloodshed and starvation as the front moved across hundreds of thousands of square miles. As the dust settled without a clear winner though many losers, self-determination became the topic of the redrawn maps. A new line was drawn between France and Germany, though neither party rested easily upon it. New nations were born in the east, granting sovereignty to the Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Albanians, Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, and Finns; even the Ottoman Empire collapsed into Turkey with its further lands being claimed largely by Britain. The British hoped to add the Middle East to a great chain ensuring connection with India, but these states, too, would all see their own efforts toward independence. France turned its attention more toward its colonies overseas, but Germany remained focused on Europe, building up an impressive congress through diplomacy and economics, arguably "conquering" everything east of the Rhine through new means of banking and legal authority instead of calculated military might

No comments:

Post a Comment